Curious Citations of Forgotten Lore

A common trope in fantasy and science fiction is the ancient civilization whose vast knowledge was somehow lost to the ages. The idea resonates, because whether we’re conscious of it or not, we all know that knowledge is perishable. Not only do we forget things as individuals, but societies routinely lose vast quantities of information over time. Scholars estimate that 90% of texts from antiquity are now gone, and if you’ve ever tried to access an old computer file on a floppy disk, you know that we’re still actively losing access to old data.

Digital publishing has in fact made the problem much worse. While few people are still relying on obsolete physical formats for their data, “cloud” storage - a marketing term for saving files on someone else’s computer - is also disturbingly fragile. Losing a collection of old digital photos or personal emails could be annoying, but virtually all of the world’s research is now stored this way too, and that’s a bigger problem.

A paper published recently in the Journal of Librarianship and Scholarly Communication quantifies how the archive of humanity’s collective scientific output is faring in the age of digital journals, and the results are eye-popping. Sampling about 7.4 million scholarly publications, the authors searched to see how many of them have been preserved in at least some kind of long-term archive. They found that 28% - over 2 million papers - haven’t been placed in any identifiable repository for long-term preservation. Even those that are “preserved” are often in just one repository, a far cry from the triplicate storage strategy archivists consider adequate.

If those results accurately represent the current status of digital archives, and I suspect they’re not far off, we should all be pretty upset about it. Collectively, scientists are spending billions of taxpayer and shareholder dollars on research every year, then tossing the results onto a digital compost heap. It’s an unconscionable betrayal of trust.

This isn’t the first time people have tried to broach the subject of archiving digitally published research, but scientists and science publishers still aren’t accustomed to thinking about it. Way back in the 20th century, when research publications were all printed on paper and stored in large academic libraries, archiving was relatively straightforward; libraries just shelved the back issues of the journals. Good-quality paper stored in cool, dry library stacks will last for centuries, and there’s no technological challenge in accessing it: just open the old journal and look.

Digital publication is completely different. Digital file formats often change, rendering “standard” files unreadable just a few years after their creation. I confronted that problem in my own tiny office, and it’s much worse at the scale of a major publisher. In addition, we’ve now started publishing huge chunks of “supplementary” data in papers, often consisting of additional digital files in their own specific formats. A genome sequencing paper, for example, could have terabytes of extra data accompanying it, readable only with current systems.

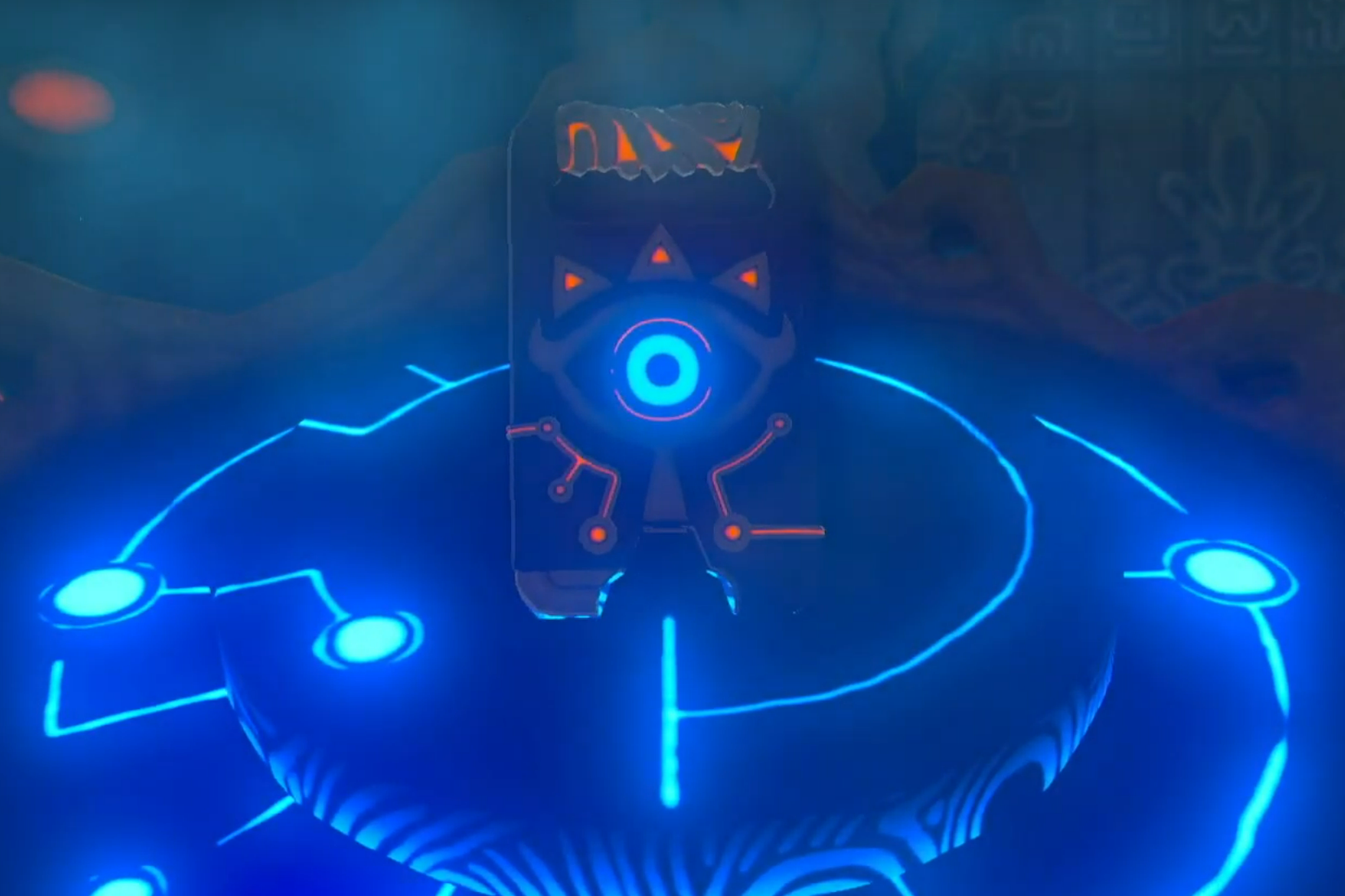

Powerful technology from an earlier age; too bad we lost all the research that went into it.

Powerful technology from an earlier age; too bad we lost all the research that went into it.

This matters. We’re building an entire world atop scientific breakthroughs that are happening every day, but leaving the primary data to rot. When someone tries to extend a line of investigation, but discovers they can no longer access the previous work on it, science stops. At best, they’ll have to waste time and money duplicating a whole series of past experiments to regenerate the old results, before finally moving foward. If the previous work relied on samples or phenomena that don’t exist anymore, then it’s simply gone forever.

Here’s an example. When I was in graduate school, I worked on poliovirus, which was then the standard model system for studying the picornavirus family. A major advantage of studying poliovirus was that there is a vast body of research on it from the early to mid-20th century, encompassing not only basic virology, but also human immune responses in the absence of vaccination. With poliovirus almost gone from the wild, thanks to widespread use of two highly effective vaccines, a lot of those findings couldn’t be regenerated. In the 1990s, though, I could just walk into the medical library and lay my hands on the primary publications from 50 years before.

Imagine a graduate student in the 2080s working on coronaviruses, perhaps trying to develop improved therapies or vaccines before the next pandemic. There was a vast body of research on one species of coronavirus from the 2020s, including troves of data on human immune responses during a novel spillover event. Unfortunately, most of that information has gone offline since the antitrust breakup of Amazon and the publishing meltdown of ‘34. Now what?

There are multiple ways to prevent that future, but they aren’t free and won’t happen automatically. One obvious option is to designate a few repositories of last resort, ideally on different continents and run by established organizations. PubMed and EuropePMC are good candidates, and I’m sure there are others. To archive the entire output of the world’s scientific enterprise, though, these efforts will need funding and staff dedicated to that specific purpose, and insulated from short-term politics and budget cuts.

The organizations that fund and supervise science should also get a lot more uptight about data preservation. If grant-givers, drug approval agencies, and tenure review committees start insisting that researchers archive their results properly, we’ll see major behavior changes.

Digital publishing is still new enough that we have time to implement these changes, before today’s bad habits become tomorrow’s traditions. Will we be the forgotten forebears whose powerful knowledge perished from neglect? Or will we be the honored elders who passed down our wisdom to future generations?